Ivermectin Squares Off in a New War on Cancer

Medical pioneers are putting their Covid treatment expertise to new uses. For two cancer patients, that meant 'complete clinical response.'

With this article, I begin what I hope will be a series of reports on the use of inexpensive generic drugs for the treatment of cancer. In one of the few good things to come out of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, a growing number of physicians who pioneered effective early treatments for Covid-19 is now attempting to learn if safe, off-patent drugs can also work for cancer. So far, results are promising for drugs like ivermectin, mebendazole (2SG: fenbendazole is identical to menbendazole, save for one molecule that was altered solely to increase BigPharma profit margins), and metformin, and supplements like melatonin.

I will write about this emerging movement from the the conference in Phoenix of the Front Line Covid-19 Critical Care Alliance this weekend, where cancer care will be highlighted. (I’m on a panel on censorship Saturday; join me there or watch afterward online.) Here now is the story of one patient and what it may mean for others.

John Ross was fifty-one years old when he was diagnosed, after more than a year of discomfort and growing unwellness, with Stage 3B colon cancer. A three- to four-inch tumor had almost completely blocked and broken through the organ wall; his surrounding lymph nodes were enlarged and presumed cancerous.

In May 2023, Ross started the traditional treatments offered by mainstream medicine—simultaneous radiation and an oral chemotherapy. He did not tell his mainstream cancer doctors that he was also taking, among other things, the repurposed generic drug ivermectin. The drug was famously—and wrongly—vilified as a horse medication during Covid, though it was in reality a Nobel Prize-winning “wonder drug” with huge untapped potential.

Ross and Dr. Mollie James, a functional-medicine physician who oversaw his nontraditional treatment, are modern-day medical trailblazers who might change the way cancer is treated. If they and others in a growing effort are successful, cancer care will be less painful, more affordable, and—the greatest hope—more effective. Practicing in a suburb of St. Louis, Dr. James had used ivermectin and other therapies to successfully fight Covid-19. (I wrote about her treatment of her brother in January of 2022.) She is now taking what she learned in the pandemic and turning it to cancer.

In his quest for the best care, Ross, who lives in Prescott, Wisconsin, went to two major cancer centers in the Midwest. He underwent a battery of blood draws and diagnostic tests and consulted at least a dozen physicians. But only Dr. James found and treated, he said, a low magnesium level, a Vitamin D level that was acceptable but too low, Dr. James believed, for challenging cancer, and, most critically, severe thyroid dysfunction. Nobody had tested for this, he said.

“I don’t know how you are standing here today—I’ve never seen blood this bad,” Dr. James told Ross after his thyroid result came in. First, she said, “I want to get you as healthy as possible before treatment.” Starting three weeks before radiation and chemotherapy, Ross began, along with ivermectin, infusions of high-dose Vitamin C and glutathione; major auto-hemotherapy, also called ozone therapy; and hyperbaric oxygen therapy, along with supplements like high-dose melatonin.

In the ensuing nearly six weeks of radiation and chemotherapy, oncologists, and others caring for Ross remarked repeatedly on how well he was doing. “Even the (radiation) technician, at the last week of treatment, made comments how this is so abnormal to have somebody that wasn’t dealing with any of the burns or anything like that,” including hair loss, Ross recalled.

The clincher, however, came in Ross’s MRI and CT scans in July of 2023. After twenty-eight radiation and chemotherapy treatments and nearly three months of the ivermectin protocol, “Ninety percent of his tumor had turned fibrous, meaning into scar tissue,” Ross’s wife, Roxanne, told me. “And the lymph nodes were half the size,” John added. An oncologist’s report called that an “excellent response.”

Dr. James has seen this outcome twice in almost identical colon cancer cases. Both were men in their fifties with advanced lower colorectal disease. One patient, John Ross, went the traditional route as well as taking the path offered by Dr. James. The other patient, who declined an interview for this article, rejected mainstream medicine and went with ivermectin and assorted other therapies.

The outcome for both, Dr. James said: “Complete clinical response with no surgery.”

The Possibilities

Two years before Covid, researchers analyzed published data that strongly suggested ivermectin could be repurposed, namely put to another off-label use, for cancer. In about twenty laboratory studies, ivermectin was found to inhibit cell proliferation and induce “apoptosis”—cell death—in cancer cell lines of the breast, prostate, ovary, head and neck, colon, and pancreas. In six studies in mice, the drug was effective against glioblastoma, leukemia, and breast and colon cancer. Based on these studies, predictions were made that ivermectin could be employed safely and soon.

“The in vitro and in vivo antitumor activities of ivermectin are achieved at concentrations that can be clinically reachable based on the human pharmacokinetic studies,” stated the 2018 article in the American Journal of Cancer Research. “Thus, existing information on ivermectin could allow its rapid move into clinical trials for cancer patients.”

That has not happened—yet. In a system driven by pricey, patented pharmaceutical products, there is little money to be made on ivermectin or any other promising generic drug. According to a study in 2016, six months of late-stage breast cancer chemotherapy cost $71,000, excluding the surgeries, radiation, and hospitalizations such cases may demand. The cost of cancer care is expected to rise 34 percent by 2030.

A seasoned group of expert doctors—often sharing their experiences in chat groups, tweets, and texts—is challenging the American model of cancer care. One patient at a time, they are using safe, off-the-shelf drugs, often alongside traditional therapies. I know of losses to cancer among their patients. But I also know of unexpected wins.

Dr. Paul Marik is a widely published critical care physician and author of a book on the potential of so-called repurposed drugs to prevent and treat cancer. Dr. Kathleen Ruddy is a retired cancer surgeon who trained at Memorial Sloan-Kettering and cared for 10,000 breast cancer patients over a thirty-year career.

These two eminent doctors have teamed up in the generic-drugs-for-cancer movement, in which Ruddy is already collecting data from doctors in the field like Dr. Mollie James. They discussed the potential for Ruddy’s “observational study”—analyzing results to see what works—and for the movement generally in a recent webinar of the Front-Line Covid Critical Care Alliance.

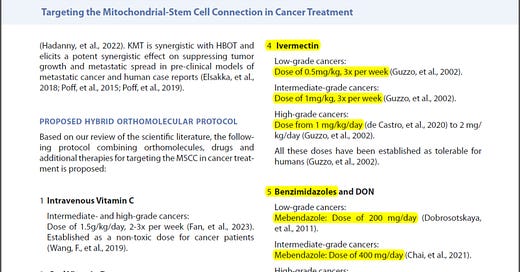

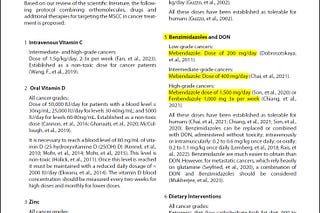

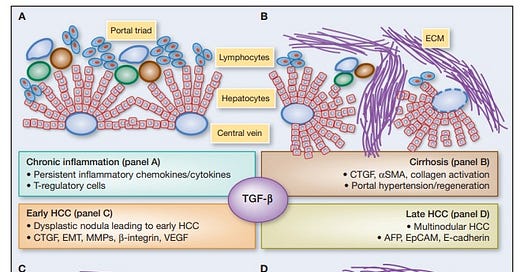

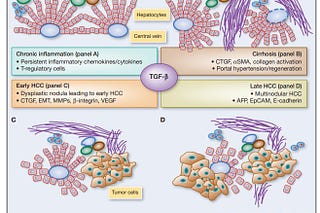

Mebendazole and ivermectin, both antiparasitic drugs, doom cancer cells by disrupting the biochemical pathways on which they depend, Marik explained of the research. “They act on tumor stem cells and the tumor microenvironment. Unlike chemo, which only targets rapidly dividing cells, both ivermectin and mebendazole have been proven to act on multiple tumor pathways involving multiple different cancer types.”

“In the pre-clinical data, the twenty years of research that Paul is referring to,” Ruddy said, “there is not a cancer type that has not been impinged upon in terms of its growth and proliferation when exposed to ivermectin. Not one. Not one,” she said, gesturing with her index finger. All have succumbed, to varying degrees, when exposed to ivermectin.

“You have an anti-parasitic drug, which is cheap and completely safe and has data to show it affects almost every kind of cancer type,” Marik responded.

Their enthusiasm aside, both physicians are also equally cautious about overstating the possibilities.

“We don’t use the word cure,” Marik told me. “I think with cancer, that’s a really bad word.” Rather, improved quality of life, chances of remission, and prolonged survival rates, he said, are the goals.

A Better Way?

Told that 10 percent of his tumor remained viable, John Ross started a second round of chemotherapy in late August of 2023, receiving one infusion followed by two weeks of oral drugs—in six two-week cycles with a recovery week between. Within twenty minutes of the first infusion, he experienced intense sensitivity to heat and cold in his mouth, hands, and feet; later, he had cramping and muscle spasms so severe he thought he was having a heart attack.

“John was absolutely miserable,” Roxanne said. Ross quit the infusion after the third dose when an oncologist told him the infusions were only contributing 10 to 15 percent to the effectiveness of the regimen. Five months later, Ross still feels numbness, cold sensitivity and burning in his feet, side effects he said doctors mentioned but “made it seem insignificant.”

“When they tell the patients you need to do this,” Dr. James said, “they definitely underrepresent the side effects and overrepresent the outcomes. If people knew their feet were going to burn for the rest of their lives with neuropathy”—a prospect Ross faces—“that chemo makes them sick, they lose weight, they can’t function…,” she trailed off.

With alternative therapies, she continued, “They can keep working. They aren’t sick all the time. They don’t look sick. Instead of fighting the cancer, we’re building up their body.”

After that experience, Ross pulled back. He reduced the oral medication, taking six pills daily instead of the prescribed ten.

He also did something else. Early that fall, he switched from ivermectin to fenbendazole, a medication used to treat parasites in animals, which, Dr. James said, he opted to take and obtained himself. Fenbendazole has shown effectiveness in three human cancer cases and in laboratory experiments on ovarian and colon cancer cells.

When the second set of scans were done in November, no cancer was found. Some “high-grade dysplasia,” a cancer precursor, was detected in biopsied cells—a possible outcome, a gastroenterologist told Ross, of the radiation treatments. Doctors want to surgically remove part of the colon, and the Rosses are weighing their options. They are thankful for the chance encounter that led them to Dr. Mollie, as they call her.

“I had fairly advanced cancer, and I feel good,” Ross, now fifty-two, told me as he drove home with Roxanne and their two sons, nineteen and twenty-one, from Jackson Hole, Wyoming, in late January. “I was just on the mountains snowmobiling. I’m an active person. I feel good.” Photographs show a man that doesn’t look like he has cancer.

He still takes ivermectin, fenbendazole, and much of the rest of the alternative protocol. The only side effect he experienced was feeling “a little tired” after Vitamin C infusions. He is back to full-time work as the superintendent of a large construction firm.

When I asked if he would share his story, he responded quickly. “If it can help somebody else, we’re all for it.”

They want you dead.

Do NOT comply.

These stories give me so much hope! Thank you for sharing it with us. 🙏❤️

Hi. Really appreciate these stories and testimonies. I am a survivor as well but wanted to point out a great book for those who seek to understand cancer pathways first published in 2018 by Jane McLelland who has survived cancer twice. Titled How to Starve Cancer, it offers up a plan and her own research to understand how to interrupt cancer cells ability to nourish themselves and how to repurpose drugs to act on those pathways.